According to the Coalition for African Research and Innovation (CARI), the proportion of researchers in the African population is 25 and 28 times lower than for the United Kingdom and the United States, respectively. The percentage of Africans pursuing graduate studies is three times lower than the global average, with similar gaps in facilities and equipment necessary to conduct cutting-edge research.

Strengthening research capacity will help produce a global pool of researchers who can use current knowledge and techniques to develop strategies, tools and methods to tackle complex problems worldwide (WHO 2016).

ResearchRound’s quest is to push the boundaries of the applications of Africa’s collective genius. To achieve this, we need to empower enough people (researchers) to ask the big questions and provide them with the instruments to investigate and answer some of these big questions. This was the genesis of LUNE ONE.

Background

Decades of underfunding research in Africa have lowered the quality of African researchers. Researcher motivations have switched for economic reasons. University postgraduates are keener to obtain a degree and get a job. Many of those who remain in the academic system rely on job security and do their best to keep moving up the academic ladder. For some, that means sporadic research publications without depth and direction. This has resulted in a technically weak research workforce and pipeline that struggle to provide new knowledge/or insights to support the country’s short and long-term development. ResearchRound’s big audacious goal is to redevelop a responsive, resilient, and proactive research workforce. We are starting with capacity development programs like the LUNE ONE research fellowship.

- What is LUNE ONE

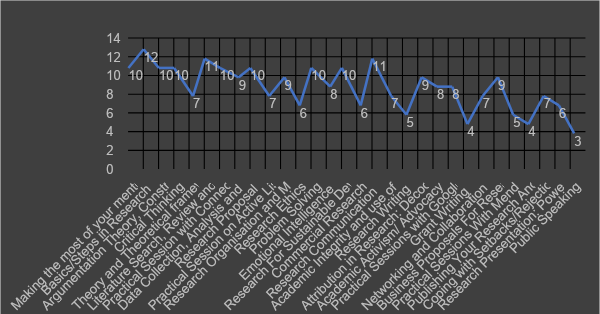

LUNE ONE research fellowship was designed for aspiring African researchers (undergraduates and early post-graduates) to build their basic research foundations. Over 4 months, participants engaged in over 30 classes on various research topics, 2-month-long mentorship and worked collaboratively on several research projects which they presented at the final program workshop. The program featured:

- 32 CLASSES on various topics like Literature review to Research Strategy.

- 4 MENTOR SESSIONS

- 6 REFLECTION SESSIONS

- 1 RESEARCH PROJECT

- 1 PRESENTATION WORKSHOP

- 1 RESEARCH REPORT

This was our pilot, and we were guilty of including a lot of variety in the main course.

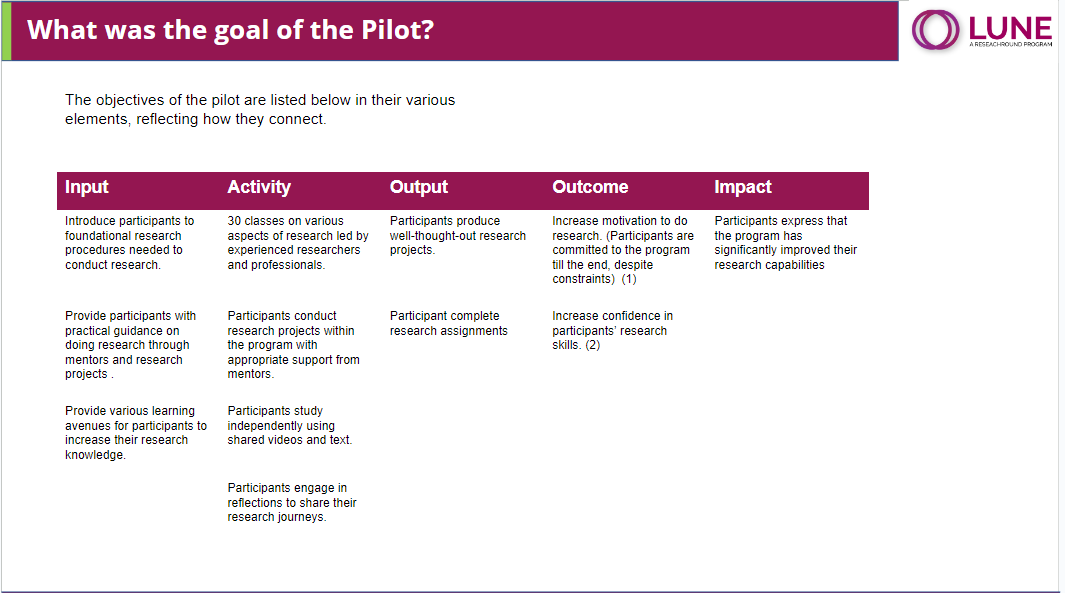

2. Objectives for LUNE ONE

The goals for LUNE ONE were

- Test our design for research capacity development by asking key questions like

- What components are essential in supporting research training?

- What methods of delivery work?

- Can we effectively train virtually?

- What depth is required and for what level?

- How effective is our current approach?

- What is the best way to reach research enthusiasts?

- Develop a more fitting theory of change for our work at ResearchRound. See the test TOC below. Through our engagements during the pilot, we hoped to learn more about the gaps researchers face in doing quality research.

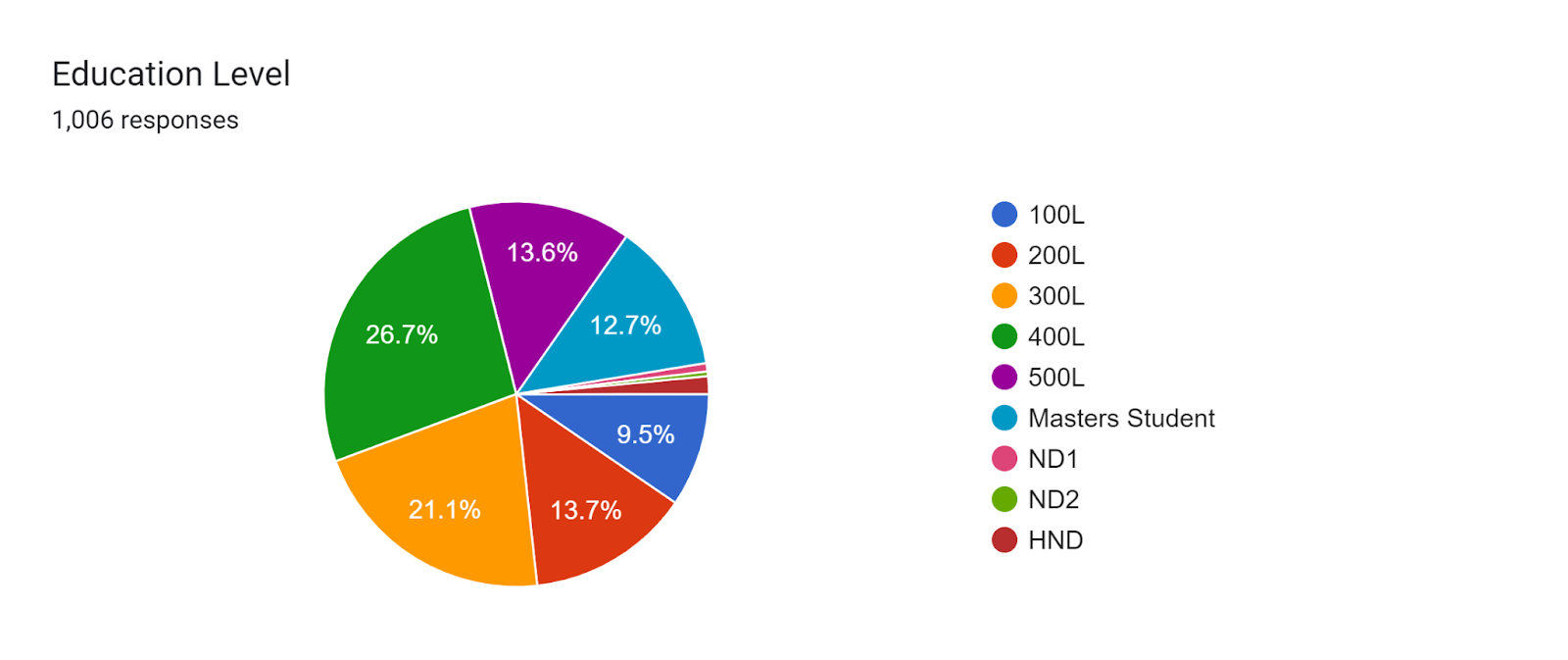

3. APPLICATION PROCESS

We opened a call for applications from March 6 2023 to April 5th 2023. We received 1000 applications across 110 tertiary institutions (including 83 universities). Applications were open to undergraduate students and early postgraduate students.

What we learnt here:

- The design of our comms materials played a strong part in attracting applicants.

- More than 70% of 216 people who filled out the post-application survey were unaware of any program by their institutions that prepared them for their research journey.

- We had questions about whether the small incentives were instrumental in driving more applications.

- While we ran no ads, the call for applications was shared across multiple university groups. This was more effective than social media efforts. We also had situations where more senior researchers and supervisors recommended the program to their students.

4. ONBOARDING

12 participants from 9 universities joined the program including 4 post-graduate students in May 2024.

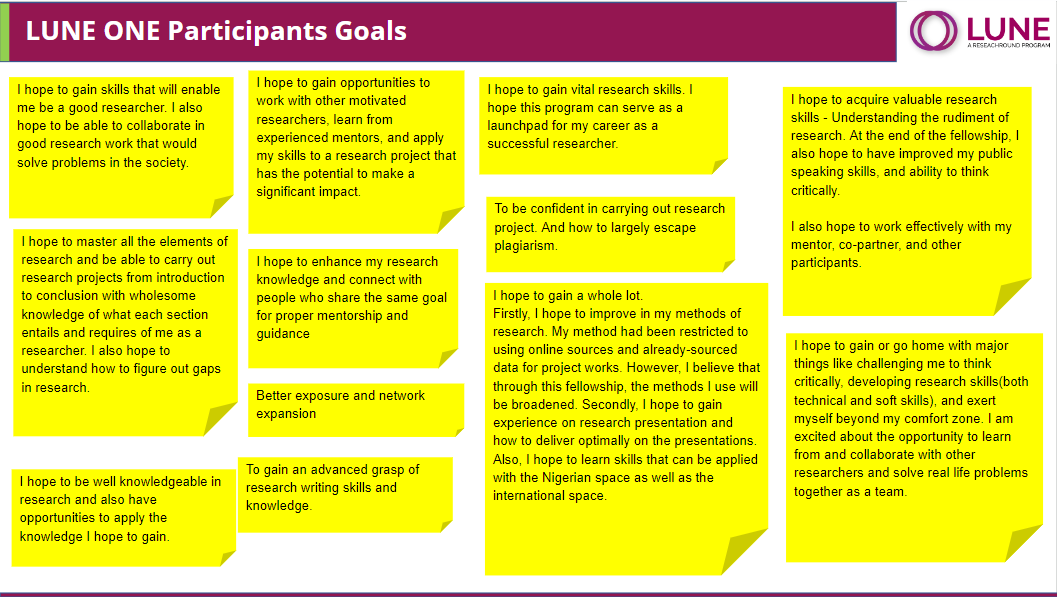

I had a one-on-one call with each participant to set clear expectations during the onboarding. I shared with them that this was a learning experience for the organisers and the participants. However, they should look forward to an excellent experience. We followed this up with a Setting the Scene session to emphasise expectations. Participants completed a baseline survey which included sharing their goals for the program.

As part of the onboarding experience, we also mailed all the participant a welcome package from ResearchRound, which included branded items like shirts, notebook, pen, stickers etc. Participants also received a digital copies of the participants’ handbook.

5. PROGRAM DESIGN

Designing a successful program required

- Curriculum design

- Recruiting facilitators and mentors

- Class scheduling

- Participants guides

- Evaluation forms

- Participant and faculty communication and management

- Documentation

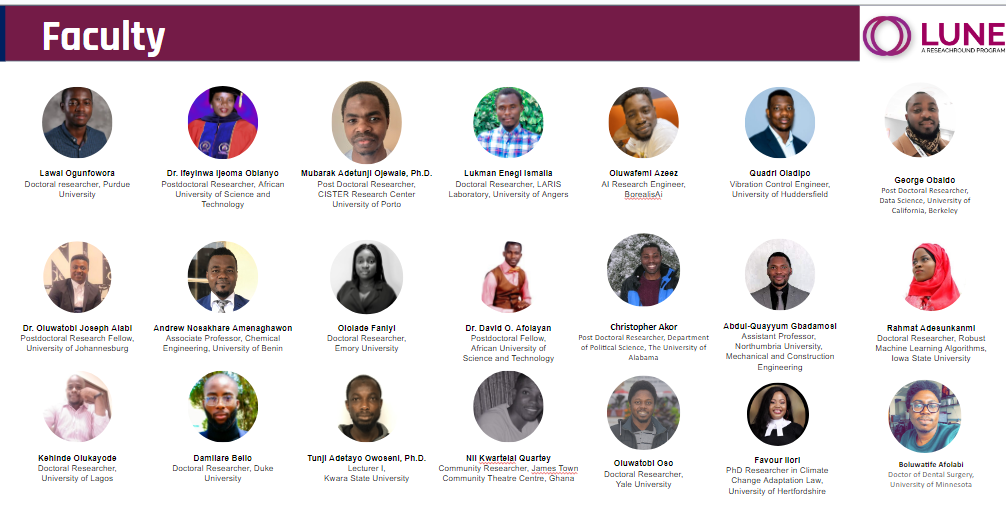

6. RECRUITING AND ONBOARDING FACILITATORS

After outlining the curriculum, we did a call for facilitators and mentors and those who were interested sign up. We also asked for recommendations from people in our network. Thus the final list consisted of faculty members who voluntarily indicated interest and those we contacted through recommendations. Each faculty member had onboarding sessions to share with them the goal of LUNE ONE and what expectations were for their involvement. Each facilitator was given one month to develop their slides, but were each given a template for their presentations. Templates contained links to readings about the subject, the objectives and expected outcomes of the class, and duration for delivery. Most facilitators submitted their slides within the required development time and worked on feedback we provided afterwards to make the presentation more suited for the class. This process was managed by the Curriculum manager and Faculty manager.

What we learnt

- Facilitators found the onboarding exercise useful in building context around the program.

- Facilitators found it very useful that we outlined the objectives for their sessions.

- Facilitators found it useful that we provided templates for them to fill out for their sessions. Although some facilitators did not use the template, they were in a small minority. There is also a higher chance that those who couldn’t deliver their presentation on time wouldn’t use the template.

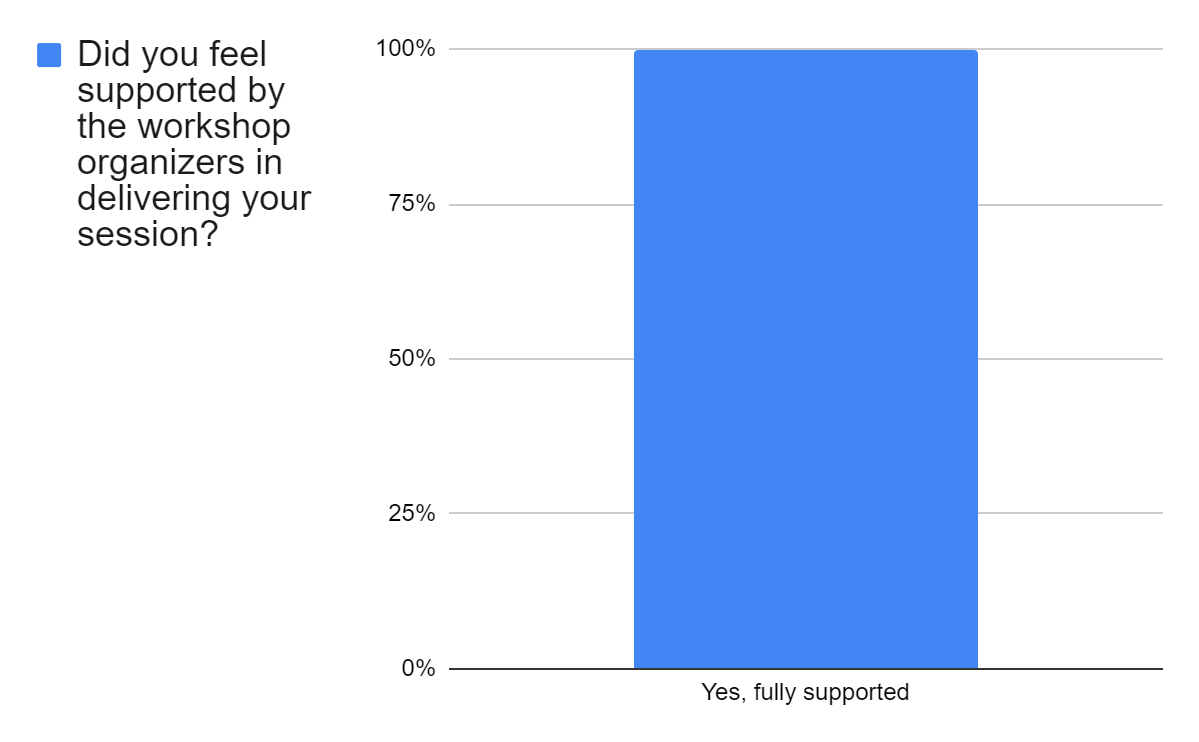

- Facilitators found the overall experience very supportive.

7. THE PROGRAM

LUNE ONE would not be possible without the esteemed support of the faculty who delivered each of the classes on research, as designed into the curriculum.

The first sessions started in early May with an introduction to LUNE ONE. Following that, we had three 1-hour sessions per week for 12 weeks. Participants joined as many sessions as they could.

Participants were provided with airtime for internet access to attend the sessions. This was done weekly. This made it easier for participants to join the sessions. Participants also received a few souvenirs including shirts, water bottles, notebooks, pens and stickers. We assigned a participant administrator to keep up with the participants and follow up on their needs. Participants valued the various support we provided during the program.

LEARNINGS FROM THE CLASS SESSIONS

- Rescheduling – Participants were less likely to attend classes that were rescheduled.

- Participants felt that 3 sessions per week were a lot, which increased the likelihood of absenteeism.

- Participants also felt the program was packed and fast-paced so they sometimes could not keep up with the amount of things they were learning.

- Participants enjoyed the learning opportunity from more experienced researchers and found the guidance valuable.

- There could be more opportunities for participants to collaborate during the program.

- Feedback was generally positive from participants who were committed to the sessions.

- Strong follow-up with participants managed the attendance outcomes.

8. MENTORING

The goal of the mentoring project was to help the participants

- Imbibe better standards working on a research project

- Demonstrate knowledge learnt from the classes

- Build new relationships with more experienced researchers

The mentoring started one month after the classes had begun. We matched two participants to one mentor each. There were six mentors in total. In some instances, we paired two participants from similar fields of study, and in other cases, we matched participants from different fields of study. One key output of the mentoring exercise was a research project which demonstrated knowledge gained during the program. In one case, our participants joined the research team of one of the mentors to author a publication which was submitted for peer review.

WHAT WE LEARNT

- The level of commitment of the mentors was very influential in a successful mentoring relationship.

- The most successful mentorship relationship, based on participant satisfaction and outcomes, was where the mentor developed a guide for mentoring the participants and followed the mentoring guide judiciously while documenting key outcomes of their engagements.

- Participants felt that mentoring was a critical piece of the learning process.

- The most productive mentoring engagement involved mentors and participants from similar fields.

9. EVALUATING THE PROGRAM

We collected data throughout the program to help us monitor and evaluate the program. Data collection channels included:

- Baseline Survey – Participants completed the survey before the program began to share their research status and goals.

- Post-Class Survey – Participants completed a survey after each class.

- Class Summaries

- Post-Program Survey – When the program ended, participants completed a survey to give feedback about the whole program.

- Facilitators/Mentor Survey – Facilitators and mentors completed a survey after their sessions.

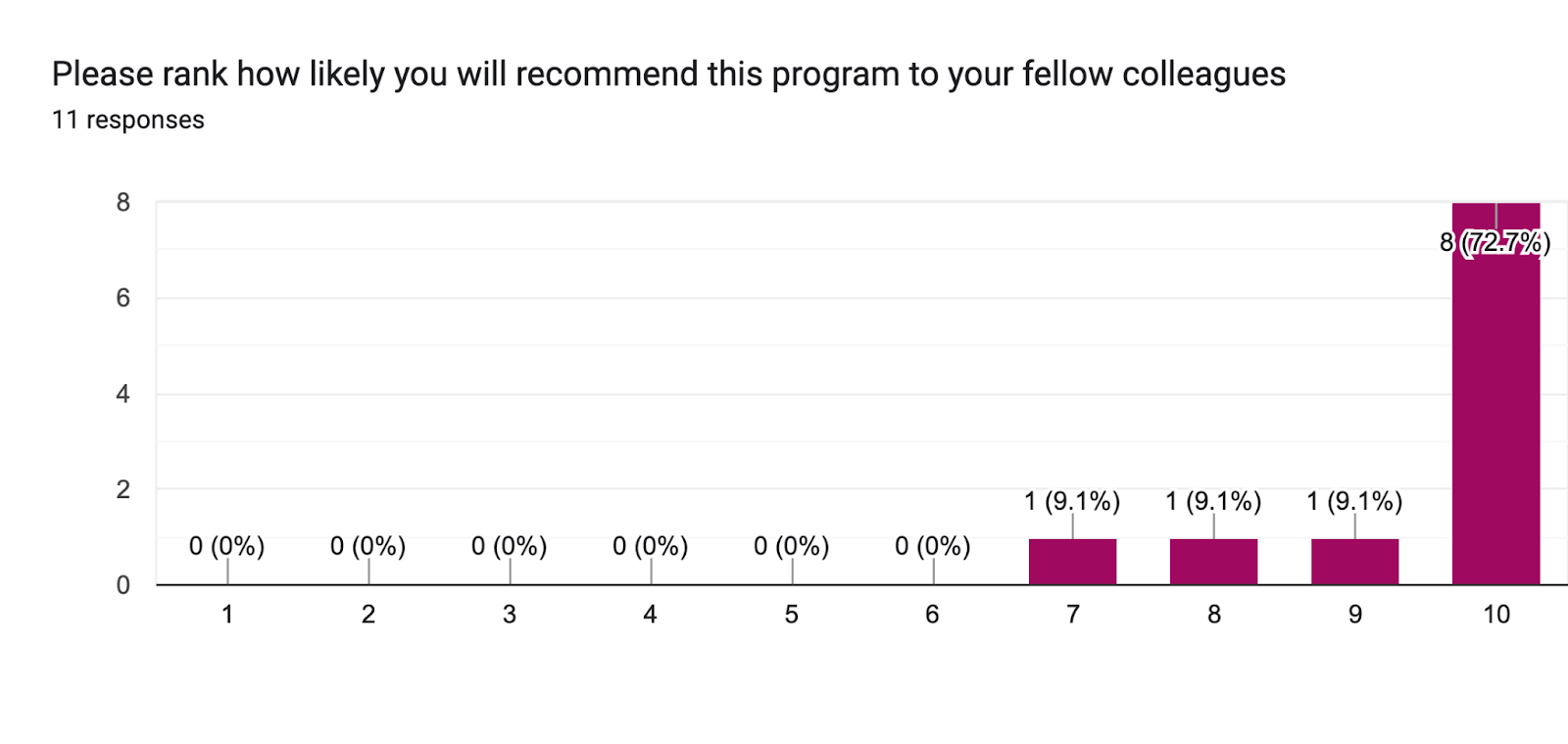

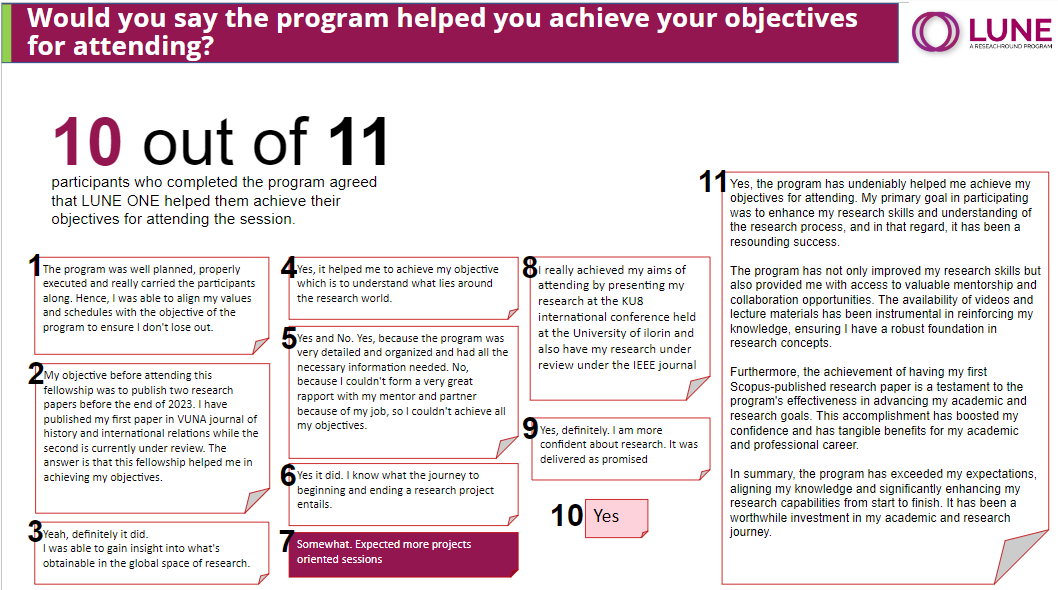

At the end of the program, participants witnessed a dramatic increase (30%+) in their confidence in research due to the new skills and motivations they gained. They also strongly recommended the program. We collected qualitative feedback as well to contextualise some of their feedback. Please see the images below to read them.

10. TESTIMONIAL

As one of the inaugural participants of the LUNE ONE program, Chime shared the following:

- Why she applied to the LUNE ONE program – What attracted her to ResearchRound’s LUNE ONE program

- Why she stayed on after attending the first class

- What she liked best about the program

- Why she would recommend the program to other people

- What made her feel confident about research after LUNE ONE

- What she will do differently after LUNE ONE

Chime joined the program as an assistant lecturer from the Federal University of Technology, Owerri. Chime is now pursuing her doctorate in South Korea.

11. CONCLUSION AND NEXT STEPS

The program was very beneficial for all the participants. We successfully answered many of the questions we asked at the beginning of the pilot. Amongst these learning, key takeaways included:

- Participants would find more niche programs beneficial, even though they loved the general research foundations program.

- More activity-based activities especially ones where participants get to collaborate frequently.

- Fewer and better-spaced sessions might drive better outcomes. Thus, deciding what is most important, and what can be left to participants to find out on their own.

- Improve the structure of the mentee-mentor engagement.

Due to the above takeaways, we are keen to do the following in our next steps:

- Increase access to learning opportunities for Researchers with well-spaced, focused learning sessions open to more people.

- Fellowships will focus on more niche areas to allow us to build customized/appropriate support for participants.

- Explore more sustainable channels to keep supporting emerging researchers, including promising partnerships.

The pilot and various engagements during the period also helped align our focus/strategy as an organisation. This helped us develop three new strategic priorities central to our future work.

- Research Capacity– Expand access to research capacity development for emerging and established researchers.

- Research Uptake– Bolster the use of research in private and public organisations.

- Research Systems– Facilitate stronger stakeholder synergy, infrastructure and commitments to more sustainable and conducive research systems.

This is reflected in the draft of our updated theory of change

Keen to collaborate on future capacity programs from LUNE ONE? Please send an email to researchround(at)gmail(dot)com.