Sometime in 2017, I sat with my cofounders at my first education technology startup, and engaged in one of the numerous realizations about the product we had built. We had given so much to creating this application and had seen it eventually become a delight among the students that used it. Our app, which we called the Geniuses Social Learning Application was meant to make it easy to teachers and students to work together, especially after school, wherever they are. A student could share work with fellow students to study and they could also do the same with their teacher. Teachers should share new learning items to everyone on their timeline and group, while students can consume content from an automated curriculum.

As delightful as all these were, there was a fundamental market problem which made our application awesome but not rewarding. The problem was not in the interest of students or teachers. In fact, when students came across the application, they became so engrossed they leave us standing. The issues came instead in form of infrastructure. Students did not have enough mobile phones to enjoy this application at home, while teachers could not use a tool most students did not have access to using. More importantly, we had to give away a lot of airtime to the people who used the application. Every now and then, students messaged us to ask for money for data to use the application. Although the application consumed very little data, students could not afford to pay for data outside the regular subscriptions that only allowed them use social media apps – a provision made by telcos to offer special data packages for social media. At the end of 2017, we had to close shop. Our application was well ahead of its time. The conclusion was to wait a few more years. The alternative was to provide gadgets, airtime, strong bandwidth for our users.

In 2020, more problems came. While there was a sudden demand for digital education platforms, the users were still not ready. Infrastructure is still lacking. In addition, more of the existing infrastructure has been put to test. Even if you are able to afford internet access and power, you could still be cut off from online sessions due to bandwidth problems. Unless you intend to start a new telecommunication company and provide strong bandwidth for yourself, this is not a problem you could easily solve. For some internet access providers, their network start to misbehave once rain starts falling. This means several people usually try to get several options to keep up with live online conversations. This cost is significantly higher than pre-pandemic periods and will easily dissuade a lot of people from trying at all.

This meant while several digital education platforms existed at the start of the pandemic, they still could not take up the opportunity that the pandemic provided nor were teachers and students able to bridge learning gaps adequately during this period. Instead, as school owners try to survive the period, some are turning into new businesses. The funniest I heard while in a meeting at work, was about a school owner that took out all the desks in the school and started rearing poultry in the classrooms. The failed transition of most schools to effective online, simply uncovered the many inadequacies of the current education sector in Nigeria.

The process of learning at home had always been unsupported by most schools. All learnings are encouraged to be held in classrooms while students usually have assignments to take home, but nothing to warrant consistent communication with their peeps or teachers. It was the reason we did not gain much traction with Geniuses the first time. Instead, schools worked to provide computer labs in their schools for students use. However, many of these labs were not built to be part and parcel of students’ learning. Rather than being integral tools of students’ learning process, they were things students went to once in a while. The most techy thing many schools did was use projectors to display notes for their students – and in such funny scenarios students still had to copy down the notes instead of just being handed the printed copies. Others often only use their tech solutions to prepare for CBT exams. Thus, the pandemic was a brutal shock for many schools, rendering them incapable of providing quality education for their students.

Many of the people who enjoyed using digital platforms during the pandemic were usually students from schools that already embraced the technology before the pandemic started. There were some schools as such that had successfully integrated technology into their learning procedures. However, these schools constitute only a few of the total population that could have access to such learning opportunities.

One thing I know is that schools now understand why they should embrace digital technology for their learning activities. This is now a reference on why this is critical. Between schools, usually affluent, who have embraced digital education and those who are unlikely to use it, are a significant chunk who had some of the facilities required and have now understood more reasons why the switch is key. The chart below is not concrete data but gives some visualization on my understanding of how the market is structured.

This meant during the pandemic, thousands of schools effectively shut down, or use very inefficient platforms like WhatsApp simply to communicate with students via their parents’ phones. However, motivation waned with time. The inability of several schools to even pay their teachers during the pandemic meant very few teachers started or maintained communication with their students and kept at it. Motivation on the side of the students too waned. Learning online is not as seamless as people expected the transition.

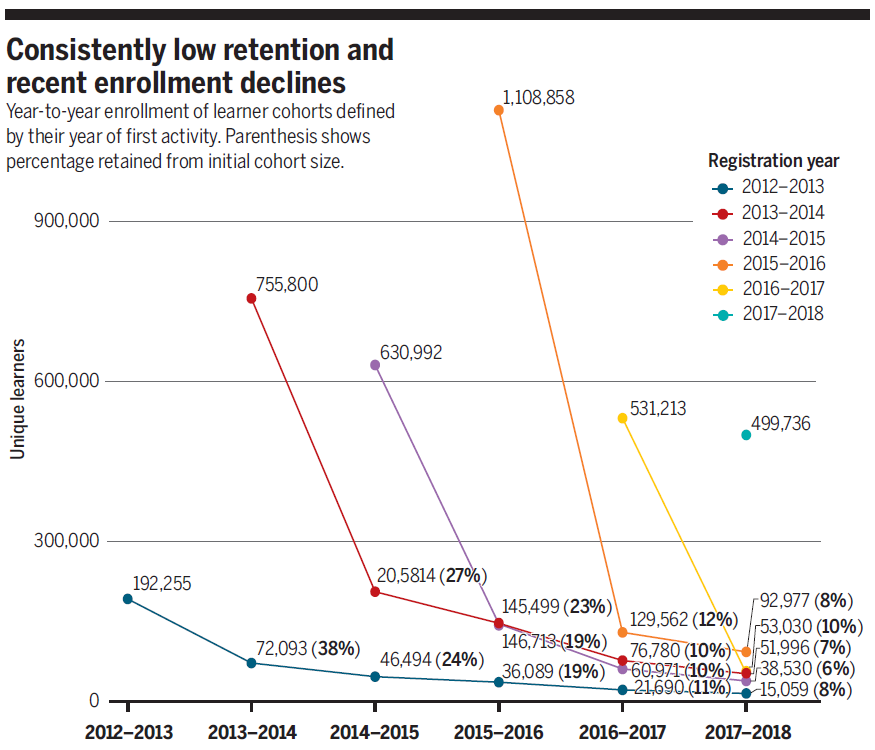

Before the pandemic, online courses had very poor completion rates. Compared with online live classes, students who took online courses had flexibility around time and bandwidth. Yet many of them failed to complete their classes. In Doug Lederman‘s article, Why MOOCs Didn’t Work, in 3 Data Points, he provided that MIT researchers document low retention rates, enrollment declines and general affluence of students to explain why massive open online course providers have largely ditched their original model.

“Among all MOOC participants, 3.13 percent completed their courses in 2017-18, down from about 4 percent the two previous years and nearly 6 percent in 2014-15. And among the “verified” students, 46 percent completed in 2017-18, compared to 56 percent in 2016-17 and about 50 percent the two previous years.”

This meant that even when students across the world had full control of how the consumed educational content, too many barely completed their classes. At the end of the article, Doug’s final sentences read

New education technologies are rarely disruptive but instead are domesticated by existing cultures and systems. Dramatic expansion of educational opportunities to underserved populations will require political movements that change the focus, funding, and purpose of higher education; they will not be achieved through new technologies alone.”

If these conclusions were reached for the global audience where a good number of people who even have access to these online courses have the facility to do them, how would we rate the local Nigerian audience where poverty is prevalent and most families can barely afford consistent daily nutrition, not to talk of education technology facilities.

Is Nigeria ready for digital education? The answer is largely no? But does that diminish the efforts people are taking to provide it? That is no as well. We need more companies and organizations with the staying power to keep pushing with their efforts to improve access to quality education – at some point things will yield significantly. A good amount of people will be able to use such services at present, but to achieve mass education, you will need much more.

Thus, the approach to bridging learning gaps with digital technology will only be successful with new processes, rather than just technology. Processes created by policy, backed by the appropriate funding. Else, digital technology solutions will continue to be knackered by the damning Nigerian system while the few who are able to score contracts to provide edtech solutions for a few will continue to bask in the positivity that will likely fail them.

Cover Photo by Julia M Cameron from Pexels